Editor’s Note: Last year, essayist and cultural commentator, Stephen Marche used natural language processing technology to uncover fake versions of Shakespeare’s works. The author leveraged Cohere’s platform, a Radical Ventures portfolio company based in Toronto, Canada. The collaboration was covered by The New York Times.

Marche continued to explore AI’s capacity to create transformative art by generating an idealized love story out of all the love stories that he has admired. Through his experiments, Marche pulls on the Frankensteinian question underlying creation, technology, and what it means to be human. In today’s Radical Reads we share an excerpt from his article in The Atlantic, “Of God and Machines,” where Marche weighs in on our future with AI (read the full article here).

All technology is, in a sense, sorcery. A stone-chiseled ax is superhuman. No arithmetical genius can compete with a pocket calculator. Even the biggest music fan you know probably can’t beat Shazam.

But the sorcery of artificial intelligence is different. When you develop a drug, or a new material, you may not understand exactly how it works, but you can isolate what substances you are dealing with, and you can test their effects. Nobody knows the cause-and-effect structure of NLP. That’s not a fault of the technology or the engineers. It’s inherent to the abyss of deep learning.

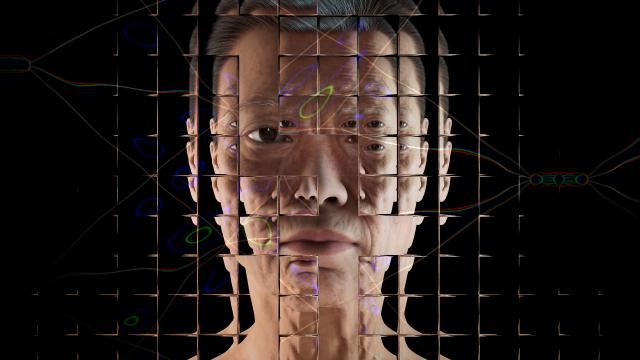

I recently started fooling around with Sudowrite, a tool that uses the GPT-3 deep-learning language model to compose predictive text, but at a much more advanced scale than what you might find on your phone or laptop. Quickly, I figured out that I could copy-paste a passage by any writer into the program’s input window and the program would continue writing, sensibly and lyrically. I tried Kafka. I tried Shakespeare. I tried some Romantic poets. The machine could write like any of them. In many cases, I could not distinguish between a computer-generated text and an authorial one.

I was delighted at first, and then I was deflated. I was once a professor of Shakespeare; I had dedicated quite a chunk of my life to studying literary history. My knowledge of style and my ability to mimic it had been hard-earned. Now a computer could do all that, instantly and much better.

A few weeks later, I woke up in the middle of the night with a realization: I had never seen the program use anachronistic words. I left my wife in bed and went to check some of the texts I’d generated against a few cursory etymologies. My bleary-minded hunch was true: If you asked GPT-3 to continue, say, a Wordsworth poem, the computer’s vocabulary would never be one moment before or after appropriate usage for the poem’s era. This is a skill that no scholar alive has mastered. This computer program was, somehow, expert in hermeneutics: interpretation through grammatical construction and historical context, the struggle to elucidate the nexus of meaning in time.

The details of how this could be are utterly opaque. NLP programs operate based on what technologists call “parameters”: pieces of information that are derived from enormous data sets of written and spoken speech, and then processed by supercomputers that are worth more than most companies. GPT-3 uses 175 billion parameters. Its interpretive power is far beyond human understanding, far beyond what our little animal brains can comprehend. Machine learning has capacities that are real, but which transcend human understanding: the definition of magic.

Read the full article here. Stephen Marche has written extensively on AI and NLP for The New York Times, The New Yorker, and The Atlantic. He is the author of half a dozen books, including The Next Civil War, The Unmade Bed: The Messy Truth About Men and Women in the Twenty-First Century, and The Hunger of the Wolf.

AI News This Week

-

10 years later, deep learning ‘revolution’ rages on, say AI pioneers Hinton, LeCun and Li (VentureBeat)

Geoffrey Hinton, Turing Award winner and one of the founders of the “deep learning revolution” that started a decade ago, believes AI’s greatest advances are yet to come. Fellow Turing winner Yann LeCun and Stanford University professor Fei-Fei Li agree with Hinton and are pushing back at those who claim that deep learning has “reached a wall.” Hinton asserts, “We’re going to see big advances in robotics — dexterous, agile, more compliant robots that do things more efficiently and gently like we do.” All scientific discoveries require further refinement. Fei-Fei Li concedes there are still important areas for improvement, such as diversifying the AI pipeline. Li hopes that the last decade of AI advancements will be remembered as the beginning of a “great digital revolution that is making all humans, not just a few humans, or segments of humans, live and work better.”

-

‘Predictive-Maintenance’ Tech is taking off as manufacturers seek more efficiency (The Wall Street Journal)

Four of PepsiCo’s Frito-Lay facilities in the US now have machine-health technology installed. Using wireless acoustic sensors attached to factory equipment, data can be transmitted to a cloud-based platform and analyzed by AI software trained to recognize more than 80,000 industrial machinery sounds at various life cycles of operations. The technology lowers unforeseen failures, halts, and additional expenditures for replacement parts. By 2027, it is anticipated that the global market for predictive maintenance technology will amount to $18.6 billion. Improvements in data sources including advanced acoustic sensors, historical and operational data, and images means the insights from predictive-maintenance technologies are only likely to get better in the future.

-

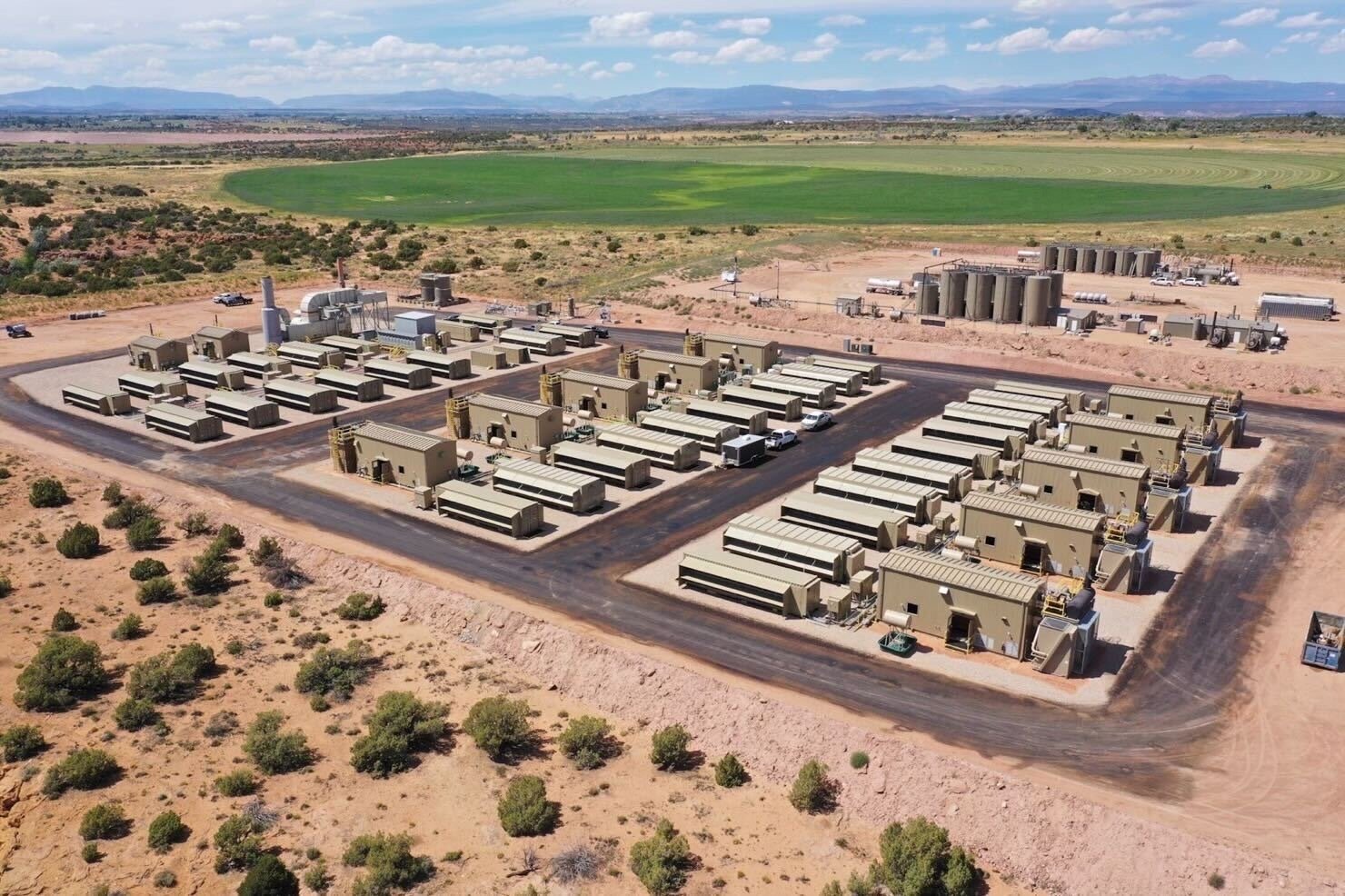

Achieving net zero emissions with machine learning: the challenge ahead (Nature)

There is growing interest in using machine learning to mitigate climate change. Machine learning could help to tackle climate change in both the short and long term. One area is using computer vision to track greenhouse gas emissions based on remote sensing and satellite data. A related opportunity is the development of improved battery-storage and energy-conversion systems. Direct impact opportunities also exist such as improving carbon sequestration techniques. Radical Ventures portfolio company ClimateAi is a pioneer in applying AI to climate risk modelling, offering best-in-class extreme weather and climate prediction combined with industry-specific operational insights. Additionally, NeurIPS and other venues now include “broader impact” statements in their publications to address the climate impact of AI.

-

An AI used medical notes to teach itself to spot disease on chest x-rays (MIT Technology Review)

An AI has developed the ability to identify illnesses in chest x-rays as accurately as a human radiologist. While radiology has been an active area of AI development for years, this is the first instance in which an AI has learned from unstructured text and performed at a level on par with radiologists. The majority of diagnostic AI models in use today were trained on scans with human-labeled results. A new model, known as CheXzero, ‘learns’ on its own from current medical records. It compares pictures to notes that experts have made in plain language, accurately predicting several diseases from a single x-ray. The model’s code has been made available to other researchers in the hopes that it may be used with echocardiograms, MRIs, and CT scans.

-

How AI Transformers mimic parts of the brain (Quanta Magazine)

Neuroscientists have harnessed many types of neural networks to model the firing of neurons in the brain. New research shows how the brain’s hippocampus closely resembles a special kind of neural net known as a transformer. Transformers operate on the principle of self-attention, where any input, be it a word, a pixel, or a series of numbers, is always linked to every other input (Radical portfolio company Cohere’s CEO and co-founder, Aidan Gomez, is one of the inventors of transformers). Transformers were initially created to perform language tasks, but they have since become quite good at other tasks like identifying photos. Recently, researchers under the direction of Sepp Hochreiter transformed a 40-year-old memory retrieval model into a transformer. Because of better connections, the model was able to store and access more memories. While researchers emphasize that they are not attempting to recreate the brain, the goal of the work is to design a device that can mimic the brain’s functions.

Radical Reads is edited by Ebin Tomy (Analyst, Radical Ventures)